How I Found the Report Cards, and How They Changed My Life

Posted Sunday, Sept. 18, 2011, at 10:12 PM ET

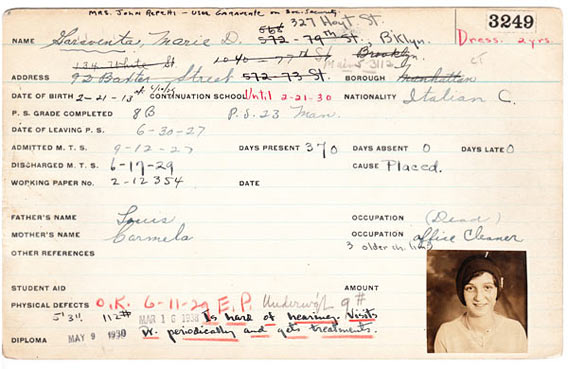

Meet Marie Garaventa.

What you see above is the front of her report card from the Manhattan Trade School for Girls, a vocational school she attended in the late 1920s, after she had finished the eighth grade. As you can see, she had a perfect attendance record?this despite moving several times, having a deceased father, and being hard of hearing.

If you click through the rest of Marie's student record, you'll see that the school's staff initially described her as "slow" and "irritable" (perhaps due to her hearing problems) but that she eventually gained confidence and made the honor roll. You'll also see that the school helped to place her in more than a dozen sewing and dress-finishing jobs after she graduated, and that at one point she was scolded for not returning to a job after her lunch break.

It all reads like the storyboard for a movie or a play?the rough outline of a young woman's life, from her mid-teens through early adulthood, with the later chapters still to be written.

Now imagine nearly 400 of these stories. Four hundred little dramas, all sketched out on cardstock. Marie's report card comes from a large batch of old Manhattan Trade School student records that I stumbled upon more than a decade ago and have been obsessed with ever since. I've spent a good chunk of my life poking around antiques shops, yard sales, and abandoned buildings, but these report cards are by far the most evocative, most compelling, and most addictive artifacts I've ever come across.

I discovered the cards in 1996 (more on that in a minute). I found them fascinating, but I didn't have a good sense of what to do with them, so for a long time I just kept them as curios and occasionally showed them to friends. Eventually, though, I decided to track down some of the students' families (including Marie's). Even after doing it numerous times, I still find it a bit surreal to call a stranger on the phone and hear myself saying, "Hi, you don't know me, but I have your mother's report card from 1929. Would you like to see it?"

While a few people have responded to that opening line with suspicion or caution, most have been gracious, and curious. They've opened their homes to me and shared their family archives. And they've been captivated by the report cards, often learning new things about their loved ones and filling in gaps in their family histories. Most of them knew very little about this vocational school their ancestors had attended.

That school, the Manhattan Trade School for Girls, turns out to have been a very interesting place. And a well-documented one, too. Within a decade of its 1902 founding, a book about it had been written and a 16-minute film about it had been shot. All of which comes in rather handy if you happen to be researching a bunch of the school's students.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. You're probably wondering how I acquired the cards in the first place. As you might expect, the story begins in a school.

![]()

Back in the mid-1990s, the gymnasium of the old Stuyvesant High School building on the east side of Manhattan became an oddly popular venue for parties. Stuyvesant High had relocated to a new building across town in 1992, but the beautiful old Beaux-Arts structure, which had opened in 1907, was still being used for various educational programs. The old school's gym could be rented out for the evening, and I found myself there several times in 1996 and '97?sometimes for media events, sometimes for private gatherings. One of the latter took place in September of 1996, when a friend of mine used the Stuyvesant gym for her 30th birthday party.

My own elementary school had been built in the 1920s, so being in an old school felt oddly familiar?the ancient radiators, the walls covered with umpteen layers of paint. I was feeling curious about the building and decided to explore a bit. In a hallway just off of the gym was an old file cabinet. A piece of paper was taped to its side. It read, "THROW OUT."

Well, if you're going to toss it out anyway ...

I opened one of the drawers and was surprised to find hundreds, maybe thousands, of old report cards. Oddly, they were not for Stuyvesant High students. They were all for teenaged girls who'd attended some sort of trade school back in the early 1900s. Many of the report cards featured small photographs of the students, and most of them were loaded with unusually vivid commentary about everything from the students' study habits to their personal appearance (one girl, who apparently had red hair, was described as a "real carrot-head"), all rendered in impossibly perfect fountain-pen script. I was immediately smitten.

I called over three friends who were attending the party and showed them my find. We were all asking the same questions: Why had the cards been kept on file for so long? Why were they now being thrown away? If these students didn't attend Stuyvesant, how did their records end up at Stuyvesant?

We agreed that the cards appeared to be very, very special?maybe even important, given the level of historical information they contained?and that we couldn't allow them to end up in the trash. After briefly flirting with the idea of taking the entire file cabinet (hmmm, where does one procure a hand truck at 10 o'clock on a Saturday night?), we each took as many of the student records as we could fit inside our jackets?about 80 of them, in my case?and congratulated ourselves on preserving a sliver of New York City history.

Old documents are always interesting, and I figured the report cards would deliver the usual tingle of voyeuristic excitement that comes with getting a glimpse into a past world. But as I examined my batch of cards in the days and weeks that followed, I realized they were no ordinary old documents. For that matter, they were no ordinary report cards. For reasons that weren't yet clear to me, the Manhattan Trade School for Girls had kept track of its students' employment history for years after they graduated, which provided a look into the students' post-school lives and also painted a striking portrait of the Depression-era labor market. (I later learned this was because the school had its own job placement office?essentially an in-house employment bureau?and had helped the students secure those jobs.) Many of the students' records also featured assorted paperwork?letters to the students from the school staff , notes from social workersand doctors on beautiful old letterhead, reports of tragic family situations, postcards from parents and other family members. Each student's file felt like a series of dots waiting to be connected.

The cards indicated that the majority of the students had been born to immigrant parents?Italians, mostly, but also lots of Eastern European Jews, some Russians, and a smattering of others. Many of their families appeared to have been desperately poor, with lots of bad luck to boot. Here was a girl whose mother had ended up in an insane asylum and whose father was "paralyzed and a drunkard." Here was one who needed dental work but couldn't afford the dentist's $3 fee, so the school's secretary gave her $1.50 to have the work started. Here was one who said she had received $3.50 for three days' work and had then been forced to leave the job because the work site was so cold "your hands almost freeze off of you."

But there were also tales of success, triumph, and joy?stories of striving and pride, of the American Dream taking shape. Reporting back to the school regarding a millinery job in which she'd been placed, one student wrote, "This is the kind of place I like. ? Our hats are always different and I can't wait until the next day starts!" Other students' files included notes indicating that they'd gotten married and had started families of their own.

What happened to these young women? How had their lives turned out? Did they keep using the skills they'd learned at Manhattan Trade? Did their teachers' assessments of them turn out to be accurate? I wanted to know.

But this was 1996. The Internet was still in its infancy; Google didn't yet exist. The prospect of trying to track down the students seemed overwhelming, especially since most of them had presumably gotten married and changed their last names. The task seemed overwhelming, so I decided to enjoy the cards for what they were and leave it at that.

Eventually my fascination with the report cards gave way to other obsessions, other projects, other collections. I put the cards away in a drawer. I never forgot about them over the years (every now and then I'd take them out and read through them, or use them for show-and-tell with friends), but I never did anything with them either. And that always bothered me.

During the summer of 2009, I began to feel a growing responsibility to do something meaningful with the report cards. By acquiring them years earlier, I had essentially become the steward of these stories, and I'd grown ashamed of what a poor steward I'd been. What was the point of rescuing the cards from a file cabinet if they were just languishing in my file cabinet?

Time hadn't diminished my curiosity about what had happened to the girls. By this point, however, I was also acutely aware that any chance of finding some of the students still alive had probably been frittered away during the dozen or so years since I'd acquired the cards.

But even if the students had passed on, I could try to find their families, their descendants. And online databases had come a long way since 1996. The tools now at my disposal made the project seem less daunting.

Before getting started, I contacted the three friends who'd taken their own bundles of report cards on that night at the Stuyvesant gymnasium and told them what I had in mind. I hadn't mentioned the report cards to any of them in at least a decade (indeed, two of them had largely drifted out of my life by this point), and each of them had moved at least once in the intervening years, so I didn't expect any of them to have saved their cards. But I thought they should know what I was planning to do.

As it turned out, they'd all saved their batches, and they were happy to donate them to my project, giving me a total of 395 student records?a huge number of leads to follow. If I could track down even 5 percent of the students' families, I'd have a lot of stories to share.

As my friends handed over their card batches to me, each one told me essentially the same thing: "I've never really known what to do with them. But I always knew I couldn't just throw them away."

![]()

What exactly do I mean when I keep referring to "the report cards"? What do they consist of, and what do they document? Here's a breakdown:

- I have 395 student records, all from a now-defunct vocational institution originally called the Manhattan Trade School for Girls and later known by several other names (Manhattan Industrial High School, the Manhattan High School for Women's Garment Trades, and Mabel Dean Bacon Vocational School). For the purposes of simplicity, I will refer to it by its original name throughout this series of articles. Click here for a detailed description of the cards as physical objects.

- Girls attended Manhattan Trade in lieu of high school, usually beginning when they were 14 or 15, and were expected to finish by the time they turned 17. The school was founded in 1902 by a group of wealthy progressives and offered one- and two-year programs in a variety of disciplines, primarily in the "needle trades" (dressmaking, sewing machine operation, millinery) and, to a lesser extent, the "brush and glue trades" (sample catalog mounting, novelty box making, lampshade making). The curriculum also stressed thrift, home economics, personal presentation, and other life skills that would help the students survive in the labor marketplace. Many thousands of students attended the school over the years, so the 395 report cards in my collection are just a snapshot of the school's operations. (We'll take a closer look at the school later in this series.)

- All 395 students were female. Most were born between 1900 and 1920, and a few in the late 1800s, which means they attended Manhattan Trade primarily in the 1910s, '20s, and '30s. They came from all five boroughs of New York City, and a few lived in New Jersey and Connecticut.

- Although I've been using the singular term "report card" when referring to a student's record, each student's file is actually a packet of several cards, usually four or five of them. Since I have 395 individual student records, this means there is something on the order of 2,000 individual cards, most of which have been filled out on both sides. Some of the packets also include additional paperwork relating the student's time at Manhattan Trade. We're talking about a lot of data here.

- The cards were not sent home with the students for their parents to review. Instead, they were for the school's internal recordkeeping?the students' proverbial permanent records. I've been unable to confirm whether the school had separate cards that were sent home for parent review, although it seems likely.

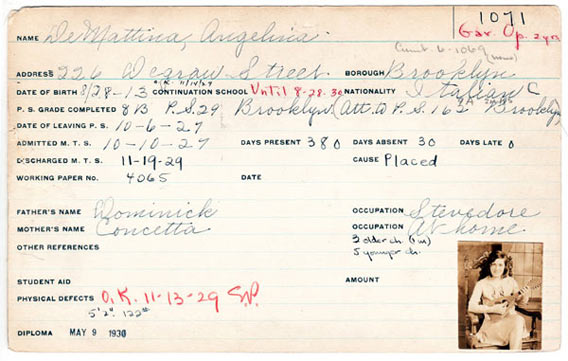

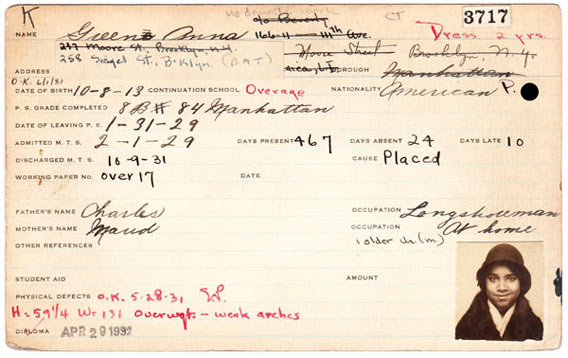

- Around 1926, Manhattan Trade began adding small black-and-white photographs to new enrollees' report cards. About 40 percent of the cards in my collection?166 out of the 395?feature these photos. Although the photos are only about an inch square, they're very expressive. Some of them are head shots and others show the student's torso or full body. One girl posed with a mandolin and another while feeding chickens in a fancy dress. A few of the shots are in color?apparently the result of hand-tinting, not color film. This lack of standardization suggests that the photos were provided by the students, not taken by the school (although a few of the shots appear to have been taken in the same setting, so maybe the school had an informal photo studio as well). A few of the photos include handwritten annotations from the school's staff, indicating that the student is actually moreor lessattractive than the photograph suggests.

- As you'd expect, the Manhattan Trade cards include evaluations and comments from teachers and administrators?mostly positive ("Conscientious, hard-working student"), sometimes negative, and occasionally downright harsh. About one student, a teacher has written, "Worst record of carelessness and forgetfulness I have ever had." About another: "Personal appearance: Not very immaculate looking." And another: "Walks around as if she were dying?absolutely pepless."

- The 395 students included a handful of black girls, all of whose cards are marked with an extremely potent symbol: a small adhesive black dot?literally a black mark on their records. This seems horrifying, but it appears to have been a warning system designed to help protect the black girls from job discrimination when the school helped them find employment. (My collection also includes one Native American student, whose card has a black dot, and one Hispanic student, whose card has a partial black dot, so the system was apparently used for all students of color.)

- Students did not receive their diplomas until they demonstrated a proficiency in their trade. The school helped them achieve this by establishing a job placement office that arranged employment for the girls after they finished their training. The girls were instructed to report back to the schoolabout their work experiences, and the employers were encouraged to report back on performance of the girls, and all of this information was recorded in the card packets. So these aren't just scholastic records?they're also employment records. Much like the teachers' assessments, comments from the students' employers run the gamut from encouraging ("Thank you for sending me such a smart little girl?she is all I would desire and does your school credit in every way") to heartbreaking ("Terrific odor of perspiration, have to lay off").

Those are the basics. But to give you a better sense of the information contained on the cards, and how to interpret that information, let's take another look at Marie Garaventa, the student you met at the beginning of this article. If you click on the thumbnails below and then mouse over the highlighted areas, you'll get a crash course in Manhattan Trade School report cards.

![]()

Now that you've gotten better acquainted with Marie, you're probably wondering what happened to her. Happily, I was able to find out. We'll explore her story, and how I was able to find it, tomorrow.

See the full report cards for the dozen students who are covered in this series. See a full listing of the 395 students in Paul Lukas' report card collection, and contact him regarding this project.

How I Found the Report Cards, and How They Changed My Life

Posted Sunday, Sept. 18, 2011, at 10:12 PM ETPaul Lukas specializes in writing about small, overlooked details?like, say, a bunch of report cards in a discarded file cabinet. He's a columnist at ESPN.com, where he writes "Uni Watch," the sports world's foremost (OK, only) column about uniform design. He plans to continue his report card research on the Permanent Record blog.What did you think of this article?

Join The Fray: Our Reader Discussion ForumSource: http://feeds.slate.com/click.phdo?i=5cb5484d1204a4c7fe0f0c4c5602cd8e

weather channel sweet home alabama the dark knight watchmen cupcake recipes cupcake recipes wilfred

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.